This is the Great Commandment, and it’s so tempting for us preachers to just preach what we already know – and we know this commandment. For many of us, such as in the Reformed tradition, this is known as a “summary of the law” that is incorporated into weekly worship as following confession. For many congregations, this is the basic grist of a mission statement or a mantra for living. A church I pass on the way to my own puts it on the sign outside, “Love God, love people.” We preachers have preached some version of it many times, and it’s tempting to preach that sermon again. But what if we come at it from a different direction this Sunday?

Matthew’s version of the Great Commandment offers us a chance to find a new angle because Matthew embeds the teaching in a series of questions, the first three from religious leaders to him, and the last one from him to them. The Revised Common Lectionary pairs the third question, the Great Commandment question, with Jesus’ question to the leaders about the Messiah. It’s unique to Matthew that these two bits of dialogue appear in sequence, and the early church thought it was significant that they should be read and understood together, as did Martin Luther (a helpful connection for those celebrating Reformation Day this Sunday). Let’s start from Jesus’ question and work backward.

Jesus asked the Pharisees, “What do you think of the Messiah? Whose son is he?” Across three questions, the religious leaders had been asking Jesus about ethics (taxes, re-marriage, greatest commandment) and now Jesus asks them about theology — he’s moving from behavior to belief. Whose son is the Messiah? The typical answer of their day is the one the Pharisees give: “the Son of David.” But Jesus is ready to push deeper. What about these lines from Psalm 110, Jesus replies, where David says, “The Lord says to my Lord?” Who is this “Lord” between David and YHWH? David must be referring to the Messiah, but how then could the Messiah be both David’s son and Lord?

Jesus thus silences the Pharisees, and Matthew moves the narrative to a new scene. But the question Jesus asks lingers, and Matthews us to pause and see Jesus as the Messiah. Asks us, because all of the verbs in this paragraph are in the present tense. What do you think of the Messiah? For those whose theological imagination races ahead, we see seeds of what will become, in John’s gospel, “the only Son who has made God known,” and in the council of Nicaea, “true God from true God,” the begotten One who came down from heaven for us and for our salvation. Whose son is he? The answer we give reflects back onto the earlier questions, as the answer must reflect onto all deep questions of life and shape our response. If we believe Jesus is the Messiah, and the Messiah is the Lord, God’s Son, then what he says and what he does is true. And that brings us back to the discussion of the Great Commandment.

Are we really able to keep this commandment, and thus the whole law of God, even its simplest and most distilled form? Are we able to love God with a fully centered and undivided self? Are we able to cherish all the neighbors who happen to cross our paths, even the ones we do not choose, or trust, or know, or who offend us? Of course we can’t, even if we try our best. We all live with divided selves, cluttered hearts, distracted minds, and plenty of neighbors that we ignore or don’t like. This is why the Reformers like Luther and Calvin saw the great commandment first as condemnation rather than simplified instructions for life.

On this Sunday, with this text from Matthew, we have the chance to preach the commandment as more than condemnation and more than simple instructions. With these two questions, we can preach good news, freedom and hope. Start with the Messiah. Jesus is the Savior who fulfills the law on our behalf. He frees us from the condemnation of a commandment we cannot keep. When we hold on to Christ by faith, we don’t need to do anything else to earn God’s approval. We are made God’s beloved children through Christ. And through him, we receive a Spirit that enables us to keep the commandment in a way we could never do without his help. As free people, God’s beloved, new persons in Christ, filled with his Spirit, we are enabled and empowered to love God completely, to love our neighbors as ourselves, and to experience renewing grace when we fall short. The commandment then becomes for us, not a burden, but a way of blessing for ourselves and the world.

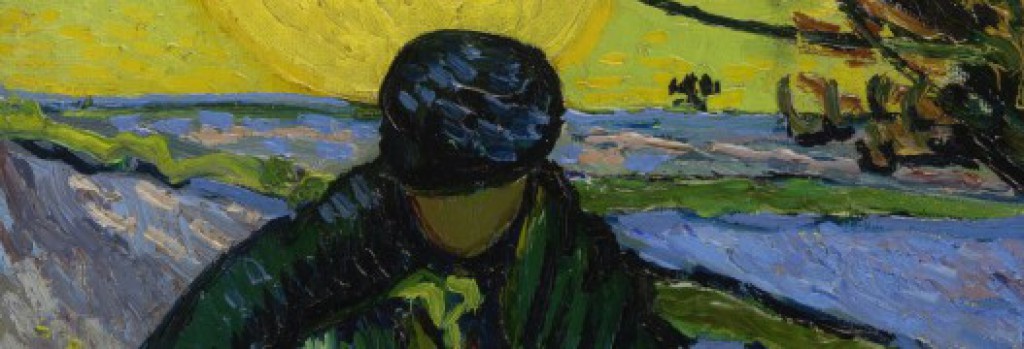

Sources: Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary; Martin Luther’s sermon on Matthew 22:34:46; art found on Vanderbilt RCL Art for Proper 25A